Study Buoyancy is a foundational concept that explains why objects float, sink, or hover in fluids. By examining the weight of a body and the volume of fluid displaced, scientists can predict its behavior in water, air, or other liquids. This powerful principle, first described by Archimedes, is not only a cornerstone of physics but also a practical tool for designing ships, aircraft, and everyday household items. The next sections guide you through hands‑on experiments, observations, and real‑world applications that bring buoyancy theory to life.

Science of Buoyancy

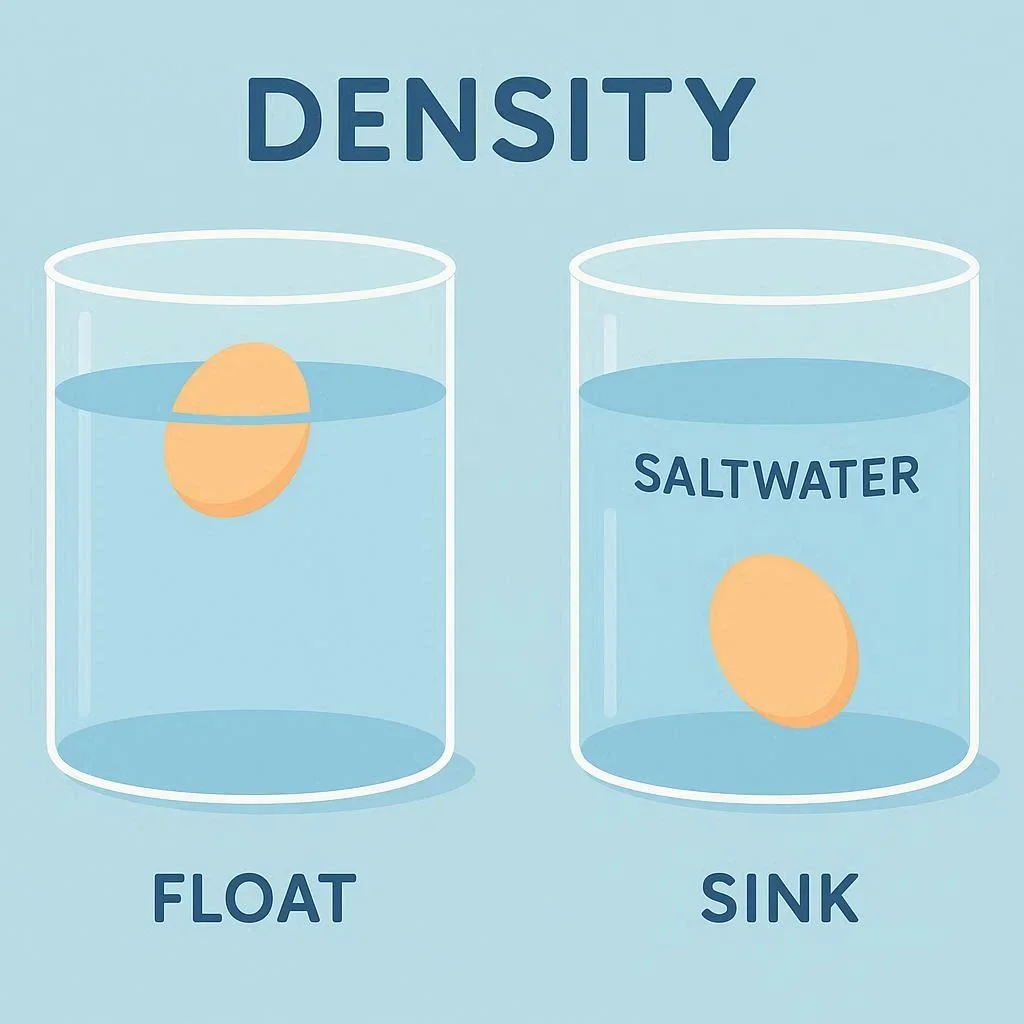

At its core, buoyancy is governed by the balance between the gravitational force pulling an object downward and the buoyant force pushing it upward. The buoyant force equals the weight of the fluid displaced, a relationship formalized by the Archimedes Principle. When the density of an object is less than that of the surrounding fluid, the upward force exceeds the downward pull, and the object floats. Conversely, if the object’s density exceeds that of the fluid, it sinks. Understanding these dynamics helps engineers calculate hull stability, aircraft lift, and even the safety of divers.

Practical Experiments with Floating Objects

Hands‑on experiments reinforce theory by allowing you to observe buoyancy in action. Below are step‑by‑step instructions for a simple classroom activity that demonstrates how shape and volume influence flotation. Gather a clear container, a variety of objects (plastic bottle, small stone, cork, wooden block), a measuring cup, and a digital scale. This will ensure precise data collection and a deeper appreciation for the science behind floating.

- Measure the mass of each object using the digital scale and record the values.

- Fill the container with water to a marked level and note the initial volume.

- Carefully immerse each object, one at a time, and observe whether it floats or sinks.

- Measure the new water level after each immersion to determine the displaced volume.

- Calculate the density of each object by dividing its mass by its displaced volume.

- Compare the densities with the known density of water (1 g/mL) to confirm buoyancy predictions.

These steps highlight the principle that an object’s flotation depends not just on its mass but on how much space it occupies in the fluid. The data gathered can be plotted on a graph to visualize the relationship between density and buoyant behavior, offering a clear, visual representation of the theory.

Observing Sinking Objects

While floating experiments are often the highlight, sinking tests are equally instructive. Sinking can reveal subtle details about material composition, internal voids, and even structural engineering failures. Using the same container, select denser items such as metal washers, small bricks, or lead clips. Carefully lower them into the water and record the depth of submersion over time. Note the changes in drag and how surface tension may affect the immediate sinking velocity.

By measuring the rate of descent, students can explore the concept of terminal velocity and how drag forces counteract buoyancy once equilibrium is reached. Such observations provide a practical context for fluid dynamics equations that predict motion of objects in viscous media. In research settings, precise sinking data are critical for calibrating sensors and validating computational fluid dynamics models.

Real-World Applications of Buoyancy

The principles taught in school laboratories extend to countless engineering and environmental fields. Naval architects use buoyancy calculations to design ships that remain stable in rough seas, while aerospace engineers calculate lift for aircraft that must counteract the forces of gravity. The same physics underlies the operation of scuba masks, oil skimmers, and even space station modules that float in vacuum.

In environmental science, buoyancy informs the spread of pollutants in lakes and oceans. For instance, oil lighter than water spreads as a slick, whereas heavier substances settle to the bottom, creating sediment layers. Understanding these behaviors assists in predicting the ecological impact of spills and designing remediation strategies. Similarly, climate scientists model the rise and fall of seawater density layers to study thermohaline circulation, a key driver of global climate patterns.

Manufacturing industries also benefit from buoyancy knowledge. For example, quality control tests for hollow components like soda cans involve checking whether the can floats, indicating correct internal air volume. Pharmaceutical packaging uses buoyant indicators to ensure dosage integrity, while the construction sector employs buoyancy data when evaluating the stability of underground pipelines in water-saturated soils.

Conclusion

By conducting straightforward experiments and observing both floating and sinking behaviors, learners gain a robust grasp of buoyancy that transcends classroom boundaries. The ability to measure density, predict motion, and interpret real‑world scenarios equips students with analytical tools essential for modern engineering and science.

Take your newfound knowledge and experiment further: try different liquids, temperatures, or even create a simple weather balloon to test atmospheric buoyancy. Share your discoveries with peers, document anomalies, and consider how this physics principle could solve everyday challenges. The next step is yours—apply the science of buoyancy and innovate.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. How does temperature affect buoyancy?

Temperature changes the density of liquids; warmer water expands and becomes less dense, making it easier for objects to float. Conversely, colder temperatures increase density, enhancing buoyant forces. Engineers use temperature corrections when designing life‑saving devices that must operate across climate ranges.

Q2. Can buoyancy principles be applied in space?

In the vacuum of space, buoyancy as traditionally understood does not exist because there is no fluid to displace. However, spacecraft can simulate buoyancy using artificial gravity generated by rotation or by magnetic fields. The principle of force balance remains relevant, though the medium changes.

Q3. Why do some objects sink even if they are made of buoyant material?

Objects may sink if they contain internal voids that are compressed or if their shape creates high drag forces that overpower the buoyant lift. Additionally, moisture infiltration or weight added from attachments can tip the density balance. Accurate density calculation, including voids, resolves such anomalies.

Q4. Is there a limit to how many times an object can float and sink?

Physically, there is no intrinsic limit, but repeated immersion can alter surface coatings, create corrosion, or introduce air pockets that change density. For practical purposes, each cycle should be monitored to detect wear that may affect buoyancy predictability.

Q5. How can I use buoyancy to create a simple water-powered machine?

By designing a system where weight is moved by displaced water, you can build a self‑powered float that drives a lever or a small turbine. Key ingredients include a sealable chamber, adjustable ballast, and an energy conversion mechanism. Experimenting with shapes and materials will refine efficiency.