Buoyancy is the upward force that enables objects to float or sink, governed by Archimedes’ principle. Understanding this principle is essential for navigating ships, designing submarines, and even crafting everyday household items that interact with water. The concept of buoyancy hinges on the relative densities of the object and the fluid it displaces. By studying floating and sinking objects, educators and engineers can predict movement, calculate load limits, and engineer safer, more efficient designs.

Buoyancy: How It Determines Floating

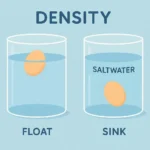

Buoyancy determines the initial state of an object when placed in a fluid; it is the result of the weight of the fluid displaced. If the object’s density is lower than the fluid’s density, the buoyant force exceeds the weight, and the object rises. Conversely, if its density is higher, the object sinks. This principle applies to countless real‑world scenarios, from a wooden log drifting to a stone sinking. The measurement of buoyancy is rooted in mass, volume, and gravitational acceleration – parameters that can be precisely measured in a laboratory setting.

Factors Influencing Buoyancy: Density and Volume

Density is mass per unit volume, and any variation in either mass or volume can drastically alter buoyant behavior. A small increase in mass while keeping volume constant increases density, making the object more prone to sinking. The volume change can be achieved by altering shape, incorporating air pockets, or using buoyant materials such as foam. One classic demonstration is a cork submerged partially in water; the buoyant lift must counteract the weight of the cork, illustrating the delicate balance of forces that governs floating. Researchers often analyze these parameters with tools like digital balance scales and volume displacement apparatus.

Quantifying Buoyancy: The Buoyant Force Equation

The equation for buoyant force (F_B) is straightforward: F_B = ρ_fluid × V_displaced × g, where ρ_fluid is fluid density, V_displaced is the immersed volume, and g is the acceleration due to gravity. This formula allows scientists to calculate how much lift an object has in any fluid. For instance, the buoyancy of a steel ball can be computed by determining the volume of water displaced when the ball is submerged. Archimedes’ Principle gives the theoretical foundation behind this equation. In practical applications, understanding buoyant force helps engineers design flotation devices for ships and rescue equipment.

Below is a concise table summarizing the variables used in the buoyancy calculation. The table clarifies the roles each variable plays in calculating the lifting force. By referencing these variables, students can perform accurate calculations during lab experiments.

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| ρ_fluid | Density of the fluid (kg/m³) |

| V_displaced | Volume of fluid displaced (m³) |

| g | Acceleration due to gravity (≈9.81 m/s²) |

| F_B | Buoyant force (N) |

Applications of Buoyancy in Design and Navigation

When constructing boats, engineers ensure that the hull displaces enough water to create a buoyant force equal to or greater than the vessel’s weight. Naval architects employ buoyancy theory to calculate whether a ship can carry its intended cargo safely. In aerospace, buoyancy principles are adapted for aircraft fuel tanks and parachutes, where air’s lower density compared to the device’s material determines stability. Additionally, buoyancy informs design choices for floating structures such as offshore wind turbines and autonomous underwater vehicles. Accurate buoyancy analysis is also critical for establishing safe emergency lifeboat capacity for passengers on commercial airlines.

Common Misconceptions About Floating

Many people assume that all objects that appear heavy will sink; however, density and shape play crucial roles. For example, a steel ball can float if its shape allows it to displace a volume of water equal to or greater than its mass. Another misconception is that all materials behave similarly under pressure; in reality, high‑pressure environments can compress gases, reducing buoyancy. Some believe that adding weight to a floating object will keep it from floating, but if the added weight is offset by increased displaced volume, buoyancy may still dominate. Educators use these misconceptions as teaching tools to reinforce the physics of buoyancy.

Experimental Demonstrations of Buoyancy

In classroom labs, students conduct experiments by filling a graduated cylinder with water and gradually inserting objects of known mass. They then record the increased water level to calculate volume displaced, and subsequently verify the density. A popular demonstration involves mixing sand, water, and a plastic container to create a quasi‑sandwich that floats due to trapped air. These hands‑on activities provide tangible insight into Archimedes’s principle. Universities often host interactive exhibitions that demonstrate how altering temperature or salinity changes water density and affects buoyant behavior.

For further exploration, National Geographic’s feature on buoyancy offers a visually engaging explanation of how objects interact with fluids. National Geographic Science Insight illustrates advanced experiments using buoyancy to design underwater drones.

Case Study: The Titanic and Buoyancy Calculations

The tragic sinking of the Titanic highlighted the importance of accurate buoyancy calculations. While the ship was designed to carry 16 watertight compartments, the iceberg’s impact breached three compartments, reducing buoyancy below the safety threshold. Maritime regulations now require double hulls and redundant buoyancy measures for commercial vessels to prevent such disasters. The Titanic’s case serves as a cautionary lesson in the critical necessity of applying buoyancy theory to actual ship design. Modern computational tools simulate water displacement and buoyancy in real time for large naval projects.

Environmental Impact: Buoyancy in Marine Life

Marine organisms have evolved various buoyancy adaptations to maintain position in the water column. Some fish possess swim bladders that can be inflated or deflated, altering their buoyancy so they can hover or dive efficiently. The distribution of plankton is largely governed by their ability to remain buoyant near the surface, where sunlight energizes photosynthesis. Scientists monitor changes in buoyancy-related traits as indicators of climate change, as rising sea temperatures can alter water density and affect fish migration patterns. Understanding these natural buoyancy mechanisms informs the development of sustainable aquaculture practices.

Buoyancy in Space: Microgravity and Floating

Unlike Earth’s gravity, microgravity environments minimize buoyant forces, making fluid behavior considerably different. In research satellites, scientists study how substances remain cohesive in zero‑g, applying principles of surface tension to replace buoyancy. On the International Space Station, experiments like the “Coffee Experiment” illustrate how liquids can form spheres due to the lack of buoyant lift. Understanding these dynamics is essential for designing life support systems that handle water and waste fluids in long‑term space missions. The lessons learned help engineers create systems where fluid movement is controlled by pumps rather than buoyancy.

Digital Simulation Tools for Buoyancy Research

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software allows researchers to model buoyancy interactions without physical prototypes. These simulations calculate pressure gradients, displaced volume, and resulting forces with high precision. Engineers use packages such as ANSYS Fluent or OpenFOAM to optimize hull designs for minimal drag while maximizing buoyancy. Universities offer free CFD tutorials that guide students through the process of setting up a buoyancy problem. With increasingly powerful GPUs, even small teams can run complex buoyancy simulations on a single workstation.

Future Innovations: Smart Buoyancy Materials

Recent advances in materials science have produced “smart” composites that can adjust density in response to environmental triggers. Shape‑memory alloys can expand or contract, altering buoyant behavior in real time. Aerogels, known for their ultra‑low density, are being tested for use in emergency flotation devices. Researchers are also developing electrically responsive foams that can detach trapped air when submerged deeper, counteracting increased water pressure. These next‑generation materials have the potential to revolutionize maritime safety, underwater exploration, and even personal flotation devices.

A NASA study on “Materials for Floating Applications” highlights how new polymers can be engineered to maintain buoyant properties under various pressures. NASA Materials Research showcases ongoing experiments.

Summary and Call to Action

Through systematic study of floating and sinking objects, we gain a deeper grasp of buoyancy that guides everything from shipbuilding to space exploration. Mastering the fundamentals—density, volume, displacement, and force—empowers engineers to design safer, more efficient structures. Whether you are a student eager to experiment with water or a professional seeking to optimize a vessel’s performance, the science of buoyancy offers universal solutions. Embrace the principles discussed, apply them to your projects, and keep experimenting with floats and sinks to unlock further innovation. Take the next step: design your own Buoyancy experiment today and witness the physics of floats in action.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. What exactly is buoyancy?

Buoyancy is the upward force exerted by a fluid on a submerged object, opposing its weight. It arises from the pressure difference created by the fluid’s density. When the buoyant force surpasses the weight, the object floats; otherwise, it sinks.

Q2. How do engineers calculate buoyant force?

Engineers apply the formula F_B = ρ_fluid × V_displaced × g, measuring fluid density, displaced volume, and local gravity. Using tools like displacement tanks and digital scale readings, they compute the lifting force for design validation. CAD software often integrates these calculations for ship hull optimization.

Q3. Why does a steel ball sometimes float?

A steel ball can float if its shape permits it to displace a volume of water whose mass equals or exceeds the ball’s mass. Trapping air within the ball or adding buoyant material creates a larger displaced volume, ensuring the upward force is greater.

Q4. Can temperature affect buoyancy?

Yes, higher temperatures lower water density, reducing buoyancy. Conversely, colder water is denser, providing greater lift. This principle explains why ice floats and why ships draft differently across seasons.

Q5. What role does buoyancy play in space missions?

In microgravity, buoyancy is minimal, so fluids behave more like droplets. Engineers compensate by sealing fluids in tanks and using pumps or surface tension to manage liquids during extravehicular activities and life support.